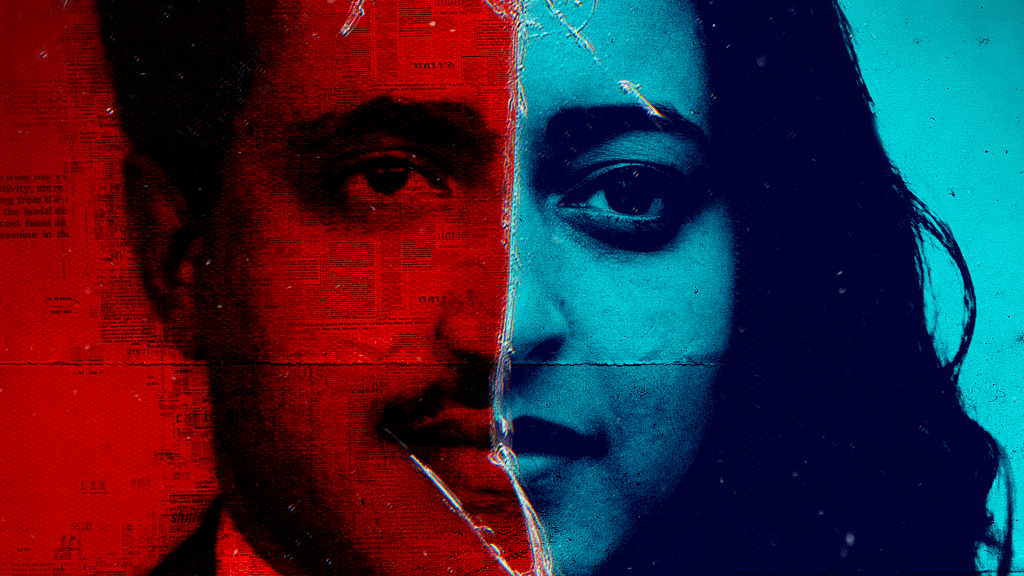

A BBC World Service Investigation

This piece is adapted from a longer investigative radio documentary script originally produced for BBC World Service.

Fifty years after the unresolved assassination of Yemen’s Foreign Minister in 1974, I set out to uncover what happened and who might have ordered his murder. I dig through scattered archives, track down long forgotten witnesses and try to reconstruct the moment that altered the course my country might have taken. In a country where history is rarely documented and often written by those in power, who gets to tell our stories, still matters.

Over the course of a year, I followed every lead I could find. From declassified US State Department cables to family diaries and private papers. From police statements buried in old Lebanese files to eyewitnesses who had stayed silent for decades. I travelled between Cairo, Beirut and Aix-en-Provence, piecing together fragments from diplomats, doctors, journalists and relatives. Not to prove a single neat theory, but to document, as rigorously as possible, how power, fear and impunity converged around one killing.

In 1974, at a traffic junction in Beirut, a gunman stepped out of a car and fired into another vehicle waiting at the lights. The shots were silenced. The attackers fled. By the time the passenger reached hospital, he was dead.

Mohamed Noman was the former Foreign Minister of North Yemen, a political reformer and an advocate for civilian rule. To many, he represented the possibility of a different Yemeni future. To others, he was a problem that needed to be removed.

He came from a family deeply associated with Yemen’s reform movement. His father, Ahmed Mohamed Noman, co-founded the Free Yemeni Movement, served twice as Prime Minister and pushed relentlessly for education, modernisation and the rule of law. He was openly sceptical of military power. Mohamed Noman inherited both this political legacy and its enemies.

By his early forties, Mohamed Noman had held several senior posts, including Deputy Prime Minister, Roving Ambassador and Foreign Minister. He was his father’s political heir and, crucially, he shared his father’s opponents.

Two weeks before the assassination, a bloodless coup took place in North Yemen. Colonel Ibrahim al-Hamdi and his allies seized power, turning the young republic into a military-led regime. Mohamed Noman, who had long argued against military rule, was suddenly out of government. He spent the following days travelling across the region, speaking publicly about the coup. When he returned to Beirut, Lebanese authorities offered him security. He sent them away.

On the night he was killed, he was travelling with his family through Beirut. At a junction in the neighbourhood of Al Zarif, another car pulled alongside them. No one heard the gunshots. The silencer masked the sound. The gunman escaped. Mohamed Noman was declared dead shortly after arrival at hospital. The driver survived.

The Lebanese police opened an investigation, but it went nowhere. Witnesses were questioned and released. No charges were ever brought. One eyewitness I located decades later still refuses to be identified, citing what he endured at the time. According to the driver, the gunman himself was killed within weeks. This was common practice in political assassinations of the period. The person who pulled the trigger was disposable.

At this point, my investigation shifted from national politics to geopolitics. To understand who might have ordered the killing, I had to situate it within the political fault lines of the 1970s. The Cold War had split the Arab world. North Yemen was backed by Saudi Arabia and the United States. South Yemen was aligned with the Soviet Union. Iraq, under the rising leadership of Saddam Hussein, was extending its reach through militant networks.

Declassified US State Department cables show that Washington was paying attention. One memo records the detention of a member of an Iraqi-backed group found in possession of silenced weapons in Lebanon around the time of the assassination. Another cites a family member’s belief that Mohamed Noman’s death was linked to documents exposing Iraqi involvement in plotting a coup in North Yemen.

It is a compelling theory. A senior Yemeni official, armed with evidence of foreign interference, is eliminated before he can act. Regional experts I spoke to noted that the use of a silencer suggested a high-level, possibly state-backed operation. Iraqi intelligence networks had both the capacity and the motive.

But the evidence does not point cleanly in one direction. A former Yemeni general from that period argued that Iraqi involvement may itself have been a decoy, obscuring the role of Yemeni officers behind the coup. Others pointed to South Yemen, whose leadership resented Mohamed Noman for renewing a border treaty with Saudi Arabia.

Colonel Ibrahim al-Hamdi also emerges as a figure of interest. Diaries kept by Ahmed Mohamed Noman record a phone call from the Interior Minister days after the coup, complaining on Hamdi’s behalf about Mohamed Noman’s media appearances. Hamdi clearly saw him as a political threat. Yet diplomatic reporting from the period portrays him as a reformer who preferred bloodless consolidation. He, too, would later be assassinated in an unresolved killing.

What emerges is not a single culprit, but a convergence of interests. Iraq, North Yemen and South Yemen all had reasons to see Mohamed Noman removed. As veteran Yemeni journalist Abdul Bari Taher put it to me, his assassination was a “common objective”.

The case was never solved. The archives in Yemen, Lebanon and Iraq are incomplete, destroyed or inaccessible. What remains are fragments, competing narratives and silence. I may never be able to write the final line of this story. But asking the question, and documenting what can still be traced, is a refusal to let the killing disappear entirely.

Link to BBC Podcast

Link to BBC Film